|

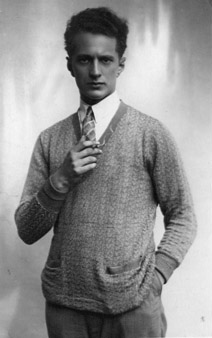

Balys Dvarionas spent his childhood in the Latvian port town of Liepāja, adjacent to Lithuania. He was born into the family of Catholic church organist and music instrument maker, Dominykas Dvarionas. Seven of the eleven Dvarionas children became professional musicians, and today most of them would merit a book unique unto themselves. For most of the children, music became something familiar, a natural extension via the instruments in the home, the church organ, and singing. Boleslovas, later called Balys (and Bolka at home and among friends - everyone in the family had a nickname), began to play the organ seriously by the age of 12. Apparently this instrument aroused his inclination towards improvisation (as did the Catholic liturgy). Balys spoke of his odd-jobs - playing in a little restaurant, and for the silent movies - where one can imagine his improvisational skills being very useful. Perhaps it was things from the cinema back then, which found their way into his subconscious, and later, in transformed shapes, affected his own work?

Everything in the biography of this man is reminiscent of a mosaic. It became a part of Balys, a sort of 'second nature', and not infrequently, something rather mysterious. A natural and distinctive part of his environment was the mosaic of languages: Lithuanian, Russian, German and Yiddish. It was the same for music, which was also like another language, and which included everything from popular tunes to Johann Sebastian. Thus the image of a mosaic would probably be applicable to the portrait of many members of this family - professionally, psychologically, representing their meandering lifestyles, and not infrequently their incomprehensible secrets and improvisations.

Following his studies in Liepāja with Latvian composer and organist Alfred Kalniņš, in 1920 Balys Dvarionas went to Leipzig where he studied piano at the local conservatory (1920-4), attended lectures at the university, and went to concerts and theatre performances. Apparently Dvarionas wasn't very satisfied with the principles of piano technique as taught by Robert Teichmüller at the conservatory, and one can see from letters written to his sister, that it was only later, when studying with Egon Petri (one of the most celebrated pianists of the last century) in Berlin (1925-6), that he learned to play with the minimum of physical effort. On the other hand, perhaps Teichmüller also had some effect in the formation of his interpretational and stylistic comprehension? For, to the very last years of Dvarionas' life, his piano playing was a joy to listen to.

Dvarionas' rudiments of professional composition were reinforced in Leipzig by Sigfrid Karg-Elert, although he graduated from the conservatory, in 1924, obtaining a diploma as a pianist. He held his first recital soon after that, in Kaunas. Upon his return from Berlin in the autumn of 1926, Dvarionas was invited to teach piano at the music school in Kaunas (the future conservatory, where he taught as professor from 1947). Once again, as if improvising, he began to direct the activities of the orchestra, and of the chamber and opera ensemble. His charming personality and his astounding musical skills - including his ability to transpose as he accompanied - immediately endeared him with both local and visiting musicians. He was a child of fortune - both in his musical 'games', as well as with the opposite sex - and remained faithful to this role (integral to his unique artistry and to his sensation of the theatrical elements of life), to the end of his days.

The beginning and end of his work as a composer were connected to the theatre. Balys Dvarionas wrote the music for six drama performances. He tried out the musical theatre genre for the first time in 1931, when he wrote one of the first Lithuanian ballets - the one-act

Matchmaking. Here, a sequence of separate dances and little scenes was completely appropriate. Unlike many years later, when he wrote the opera

Dalia (1956-1958) after Balys Sruoga's play: the coherence of form and development were replaced here by a medley of either very sincere, or a utterly trivial episodes. Opera is a tough genre, yet it appeared more successful than his Symphony in E minor, written a decade ago in 1947.

Successes and failures (more apparent in retrospect) alternated. After the aforementioned Symphony, during one of his great moments of inspiration, in the sombre year of 1948, he wrote his life affirming Violin Concerto - the first in the history of Lithuanian music. Close at hand, for some time by then, was the wonderful violinist Aleksandr Livont, with whom he became friends while playing in a trio. Was that perhaps the stimulus for his 1946 romantic piece for violin,

By the Lake? Later rearranged many times for different settings, it was one of the most popular works in Lithuanian violin repertoires. One could say that the romantic Violin Concerto, based on quotations from Lithuanian folk songs, and performed in Moscow at the initiative of the author himself, conformed to the criteria of socialist realism. But Dvarionas adjusted and in his own way went far beyond those criteria. Composed with account to Livont's energetic playing style, the piece was remarkable for its magnificent union of effort by both author and performer.

Another example of a work inspired by a performer was the song

Little Star. Perhaps only a tiny speck alongside the monumental Concerto - but a unique and exceptional one. When Vincė Jonuškaitė, an excellent opera and chamber singer of the time, handed the composer a piece of paper inscribed with a teenager's text, Dvarionas endeavoured, to no avail, to hear it as one of her songs. And yet, when, in a state of fatigue after returning from a concert tour in 1943 with Beatričė Grincevičiūtė - a blind singer emanating exceptional artistic charisma - the composer's glance fell on the scrap of paper, stuck and forgotten under glass on his writing table, he immediately heard the lines sung in the voice of Beatričė. All he had to do was sit down and put the music to paper.

It was a simple, and yet mysterious song. When he composed it in 1943, Lithuania was occupied by the Germans; prior to that he had studied in Germany, where he was in touch with a variety of German music. Could

Little Star - with some sentimental German text - not be reminiscent of the ballad of Vilja from Franz Lehar's

Die lustige Witwe, as sung by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf? Herein was the problem:

Little Star was either for Beatričė, or for a singer of Schwarzkopf's stature. The same sort of problem also applies, in a somewhat gentler form, to his Violin Concerto. When attempting interpretations other than that by Aleksandr Livont, one is inclined to think that the two magicians' spells have been dispersed by the winds of time.

There is a similar difficulty with Dvarionas' pieces for piano, and especially with his

First Piano Concerto, marked by penetrating introspection. For those who knew Balys Dvarionas, those pieces often reveal themselves not so much in the text, as through subjective connotations, often fraught with dark humour. Those interpreters who had no personal ties with the author therefore seemed to simply 'plonk away' his romantic miniatures. A fair number of those pieces, written for children and youth - including the cycles

Little Suite and

Winter Sketches - became mainstays of the pedagogical repertory. However, the music revealed itself in a different way when played by his daughter, the excellent pianist Aldona Dvarionaitė, who gradually became closer to it in her lifetime.

|

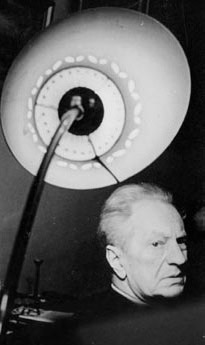

To unfold, to make music personal and inspiring - that was the lodestone of Dvarionas' piano pedagogy and conducting. He did it laconically and found interpretations which reveal everything to the very end, not interesting to listen to. Conducting also came into Dvarionas' life in an improvised way. In this area, his major training came from the wonderful Gewandhaus' symphonic concerts in Leipzig, where, as a piano student, Dvarionas watched conductors of the highest calibre. Later, though already an accomplished conductor (his debut took place in Kaunas in 1931, with his former piano teacher Egon Petri at the piano), Dvarionas went on to improve his skills, in the summer of 1934, in the International Academy for Conductors in Salzburg. After cultivating the Kaunas Radio Orchestra, which he directed until 1938, he polished his conducting technique with Hermann Abendroth in Leipzig, and came back with a second diploma from the same conservatory.

Reinforced in this way, his professional status was soon once again offered the opportunity to improvise: his friend Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, who became chief engineer in the city of Vilnius (recovered from the Poles in 1939, just prior to the Second World War), began work on the Vilnius-Kaunas highway. It turned out that a number of the workers were musicians, and the engineer recommended them to Dvarionas, who had dreamt of an orchestra in Vilnius. He founded the Vilnius Municipal Symphony Orchestra, and after it was united, in 1940, with the Kaunas Radio Orchestra, Balys Dvarionas became the first chief conductor of the Lithuanian Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra (now the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra) - Lithuania's oldest symphony orchestra.

Reflecting on his life, Balys Dvarionas once said: "Where there are no abysses, there are no mountains." And when it comes to mountains - that they can be beautiful though small, one only needs the insight to see their beauty. This is borne out eloquently, among other works, by Dvarionas' later

Micropreludes.

© Edmundas Gedgaudas

Lithuanian Music Link No. 9

Balys Dvarionas' Centenary Edition

FOR PIANO

Little Suite (1949-1952)

1. Prelude; 2. Waltz in A minor; 3. Little Windmill; 4. Waltz in G minor; 5. Little Rhapsody; 6. Theme and Variations; 7. Nocturne; 8. Dance (à la skudučiai)

ISMN M-2022-0068-1

Winter Sketches (1953-1954)

1. First Snowflakes; 2. Down the Hill on a Sleigh; 3. The Snow-Covered Forest; 4. Snowman's Brooding; 5. In the Skating Rink; 6. Little Birds in Winter; 7. The New Year

ISMN M-2022-0069-8

24 Piano Pieces

Volume 1

1. Sonatina in C major; 2. Legend; 3. Serenade; 4. Dance; 5. Lullaby; 6. Humoresque; 7. Elegy; 8. Impromptu; 9. Etude; 10. Gavotte; 11. Scherzino; 12. Mazurka

ISMN M-2022-0070-4

Volume 2

1. Grotesque; 2. Nocturne; 3. Rondino; 4. At the Old Belfry; 5. Equilibrist's Dance (Waltz); 6. Sonatina in G sharp minor; 7. Intermezzo; 8. Sadness; 9. Prelude; 10. Album Leaf; 11. Intermezzo; 12. Minuet

ISMN M-2022-0071-1

Concerto No.2 in E minor (1961)

Concerto for piano and chamber orchestra

ISMN M-2022-0088-9

(piano reduction)

Concerto No.2 in E minor (1961)

Concerto for piano and chamber orchestra

Instrumentation: pf solo-str orch. Duration: ca.25'

ISMN M-2022-0586-0 (study score)

ISMN M-2022-0587-7 (conductor's score and parts)

FOR VIOLIN

Album for Violin

Volume 1

for violin and piano

1. Impromptu; 2. Adagio; 3. Allegro giocoso

ISMN M-2022-0130-5

Volume 2

for violin and piano

1. Pezzo elegiaco; 2. Scherzino; 3. Elegia canzonetta; 4. Meditation

ISMN M-2022-0131-2

Concerto in B minor (1948)

Concerto for violin and orchestra

ISMN M-2022-0089-6 (piano reduction)

Concerto in B minor (1948)

Concerto for violin and orchestra

Instrumentation: vn solo-3222-4231-2perc-hrp-str. Duration: ca.35'

ISMN M-2022-0588-4 (study score)

ISMN M-2022-0589-1 (conductor's score and parts)